Spaces in mathematics are defined with a set of operations and specific structures. For example, if you look at a vector space, you'll find it consists of dimensions, vectors, and scalars, among other elements. It is defined by operations that must meet certain preconditions to be considered a vector space, such as closure under addition and multiplication, being associative, having an additive identity and inverse, etc. This is similar to a class in programming, which is also a structure defined by specific operations and properties. Therefore, you can represent a vector space as a class, with its properties (dimensions, vectors, scalars) and methods (operations like addition and multiplication). The preconditions are analogous to the class's rules, and the properties lead us to the next point, which is the concept of encapsulation and its difference from data hiding.

Encapsulation is like a container that holds the class, making it a self-contained entity. For example, in a vector space, one of the conditions is closure, meaning any operation performed on it must yield a result within the same vector space. This is similar to encapsulation in programming; if you have a class with properties that are private, any operation performed within the class must stay within the class (in terms of accessibility). However, is the closure condition necessary? The answer is no. For example, metric spaces do not require closure, and similarly, a class might have properties that are public by necessity. But does this mean it is not encapsulated? The truth is that encapsulation is still achieved because the class remains a self-contained entity. You can think of it as being literally encapsulated as a structure, even if it loses the property of data hiding in some cases. You can still have properties that are private.

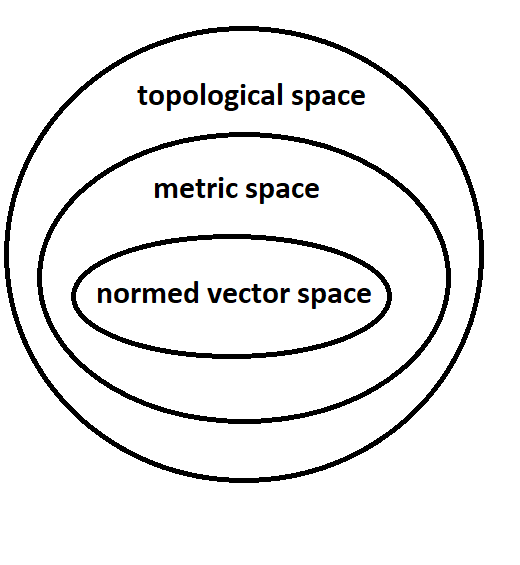

Regarding inheritance, mathematical spaces can inherit specific properties or all properties from one another, like the relationship between metric spaces and topological spaces, or any space and its subspace in general. This is the same as what happens with classes in programming, where you can inherit traits from another class. This leads us to another OOP concept, abstraction. You can derive this concept from Dr. Walid Youssef's implementation of data structures, where the developer is not supposed to know the implementation details of a data structure; they only need to know how to use it from the documentation. You use this concept daily; you do not know the implementation details of the HTTP protocol or the sort function in your programming language, but you know there is a function or method called sort, which you pass an array to, and it sorts it for you. You might not even know the algorithm it uses. This saves you time and energy and makes using the function easier.

In mathematics, you might have used vectors without knowing the conditions of a vector space, and you certainly used calculus and limits without knowing about real analysis. Abstraction also appears in the concept of generalizing your class to a broader definition. For example, if you have two individuals, a boy and a girl, you can generalize them to a broader concept: they are both persons with the same internal structure. You can then extend this to anything else. You use this concept in mathematics all the time without realizing it. Representing numbers as a,b,c is an abstraction of numbers into letters. For example, a/b represents the internal structure of any ratio of integers, where a can be 5 and b can be 20.

Check this video for a better understanding of this point if you're interested: The Mathematician's Weapon

Lastly, polymorphism: In vector spaces, you can perform an operation like addition on real numbers and complex numbers, but the implementation can be different. For example:

For real numbers in :

For complex numbers in :

The method of implementation will be different because of the imaginary part. Thus, the approach will be different for real numbers and complex numbers, although they both use the addition method but in different forms.\

In the end, this is my perspective on the topic. There might be more detailed principles for class creation and interaction that I can relate to topics studied in math, but I hope I conveyed the general idea. If I'm mistaken about anything in math or CS, please correct me.

Seth0x41

Seth0x41